Tutorial¶

Tutorial contents

Intro¶

This tutorial will start from the assumption that you already have an app which hard codes a single language. This is the ‘source language’, and we’ll assume it’s English for simplicity. You will be introduced to most of the key features of the Fluent language (although it is recommended that you also read the Fluent guide fully), and some key principles of internationalization.

If you are already using another i18n/translation solution, hopefully it should be obvious how to adapt this tutorial for your situation.

Our example will be a ‘notifications’ page in a web app. The full sources of this demo app are available, and it may be useful to have them open as you read the tutorial:

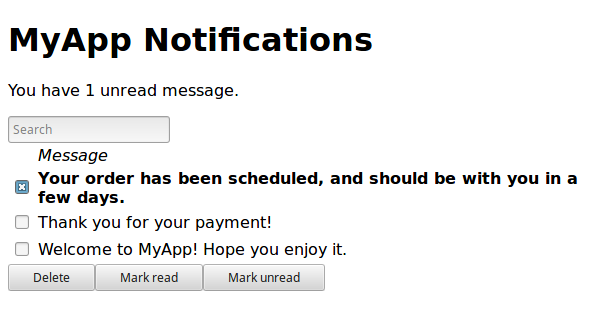

It consists of a title, a search bar, a list of notifications and some buttons for deleting or ‘mark as read’ — here it is in all its unstyled glory:

It is assumed you have followed the Installation documentation for setting up your project with elm-fluent.

One-time project changes¶

As you start to internationalize your app, there are some one time changes you’ll need, usually across your whole app. For this demo, our whole app is one page, to keep it simple, but for your app your would need to put the initial plumbing in the right place so that it applies across everything.

Our first step is to keep track of the user’s choice of locale. This could come from a server side setting that is passed into your app via flags, or it could be handled entirely from Elm code. For our demo, we will default to English and have a simple select box for changing the language, and we won’t be saving the preference anywhere (but you would need to do that for a real app).

First we need an import:

import Intl.Locale as Locale

Then we need to add a field to our model:

type alias Model = {

{ locale : Locale.Locale

-- (etc.)

}

and add a default value:

defaultLocale : Locale.Locale

defaultLocale =

Locale.en

init : Flags -> ( Model, Cmd Msg )

init flags =

( { locale = defaultLocale

-- (etc.)

}

, Cmd.none

)

We’ll want a list of locales/languages we support, with some kind of caption:

availableLanguageChoices : List ( String, String )

availableLanguageChoices =

[ ( "en", "English" )

, ( "tr", "Turkçe" )

]

Here we’ve used the localized name of the language as the caption. To make it easier for people to find their own language, and get back if they accidentally change the language to Chinese etc., we won’t translate these depending on the user’s choice of language. So this is one of the few times that we’ll hard code localized text into our Elm file (although there are other ways to do this).

For each language tag (the first value in the tuples above), we want a

Locale object as well:

availableLocales : List ( Locale.Locale, String )

availableLocales =

List.map

(\( languageTag, caption ) ->

( Locale.fromLanguageTag

languageTag

|> Maybe.withDefault defaultLocale

, caption

)

)

availableLanguageChoices

Note

The Locale.fromLanguageTag function can fail, in which case it returns

Nothing, hence the use of withDefault above. The function actually

only fails if you pass invalid language tags — it does not fail if you pass a

valid BCP47 language tag that the browser

doesn’t happen to support. We only passed valid language tags, but the

compiler doesn’t know that, so we still need the fallback here although it

won’t be used in practice.

We’ll need a message to change locale:

type Msg

= ChangeLocale Locale.Locale

-- (etc.)

And we need to handle that message:

update : Msg -> Model -> ( Model, Cmd Msg )

update msg model =

let

newModel =

case msg of

ChangeLocale locale ->

{ model

| locale = locale

}

-- etc.

We need some UI to select a different locale (you can skip this step for now if

you just want to try the system out using the default English locale). The

following is a simple select widget that will trigger ChangeLocale when

it is changed:

viewLocaleSwitcher : Model -> List (H.Html Msg)

viewLocaleSwitcher model =

[ H.text "Change language: "

, H.select []

(List.map

(\( locale, caption ) ->

H.option [ E.onClick (ChangeLocale locale) ]

[ H.text caption ]

)

availableLocales

)

]

And we need to include this somewhere in the page by adding it to the main

view function (left as an exercise for you!).

Also left as an exercise for you - if you change a page locale/language, you

should always remember to set the lang attribute on

the root <html> element, and you may want to update the document <title>

as well. You’ll probably need to do both of these using a port (because

typically these elements are outside of the root element that Elm controls).

Extract localized text¶

Now that the basic setup of the project has been done, we can begin extracting

localized text (i.e. all the English text that needs to be translated) into

.ftl files.

You need to create a locales directory to store these files. This can go

anywhere, as the ftl2elm program allows you to specify the location using

--locales-dir. We will use the default, which is to place it in the same

directory as your top level Elm source files.

Within it, create an en directory to store the English .ftl files.

Within that you can create any number of sub folders, as your project structure

dictates. We will create a file notifications.ftl directly within en

that will contain the messages for our Notifications module.

Note

You have flexibility in how you structure your FTL files and the folders that contain them. A good pattern is to structure these files and folders in a way that mirrors the rest of your project structure.

Now we will create our first FTL message. Our view function currently looks like:

view : Model -> H.Html Msg

view model =

H.div []

[ H.h1 [] [ H.text "MyApp Notifications" ]

-- etc

]

"MyApp Notifications" needs to be localized, so we’ll pull it out into

notifications.ftl. This is one of the simplest possible messages — an

entirely static string with no substitutions, which will look like this in our

notifications.ftl file:

# This title appears at the top of the notifications page

notifications-title = MyApp Notifications

Notice:

The comment which begins with

#— comments can be really important in creating.ftlfiles that are understandable and well organized. The Fluent guide has more information.For brevity this tutorial will omit comments for the rest of the messages we add.

The

notification-prefix.This is used as an adhoc prefix to indicate the component/page this message belongs to. This is not strictly necessary with elm-fluent, but has several advantages:

- If you want to combine FTL files at some point, it will help to avoid name

clashes. You may also want to use the same FTL files with other

technologies (e.g. server side rendering), and these technologies tend

to use bundles that combine multiple

.ftlfiles. - It will result in an Elm function that has a longer name, and so helps reduce the possibility of name clashes with other functions. To avoid problems, elm-fluent refuses to generate functions that would clash with default imports.

- It is the convention used by Mozilla for their message IDs, and so is a standard.

- If you want to combine FTL files at some point, it will help to avoid name

clashes. You may also want to use the same FTL files with other

technologies (e.g. server side rendering), and these technologies tend

to use bundles that combine multiple

The naming style:

The naming style used here is words-separated-with-hyphens. This is the normal convention in Fluent. These are not valid identifiers in Elm, and so are converted to camelCase by

ftl2elm. You could also use camelCase directly as your message ID e.g.notificationsTitle

Now run the ftl2elm:

ftl2elm --verbose

(See also ftl2elm --help for other options, especially if you are using a

different directory layout.)

You’ll hopefully see output like the following:

Writing files:

Writing Ftl/EN/Notifications.elm

Writing Ftl/Translations/Notifications.elm

Success!

(This tutorial won’t mention running ftl2elm again - every time you change

.ftl files you’ll need to run ftl2elm again - or, use the --watch

option and leave it running).

Let’s look at Ftl/EN/Notifications.elm. This is a compilation of our

notifications.ftl, and it looks something like this (slightly abridged):

module Ftl.EN.Notifications exposing (notificationsTitle)

import Intl.Locale as Locale

notificationsTitle : Locale.Locale -> a -> String

notificationsTitle locale_ args_ =

"MyApp Notifications"

The body is as simple as you would expect for this simple case — it just returns the string!

In addition, there is a similar function in Ftl/Translations.elm. The sole

purpose of this function is to dispatch to the correct language, depending on

the locale you pass in. It looks something like this (a bit redundant at the

moment, as we only have one language so far):

module Ftl.Translations.Notifications exposing (notificationsTitle)

import Ftl.EN.Notifications as EN

import Intl.Locale as Locale

notificationsTitle : Locale.Locale -> a -> String

notificationsTitle locale_ args_ =

case String.toLower (Locale.toLanguageTag locale_) of

"en" ->

EN.notificationsTitle locale_ args_

_ ->

EN.notificationsTitle locale_ args_

This is the function we’ll be using from our Notifications.elm module. First

some imports are needed:

import Fluent

import Ftl.Translations.Notifications as T

Then we modify the view function to use the generated function:

view : Model -> H.Html Msg

view model =

H.div []

[ H.h1 [] [ H.text (T.notificationsTitle model.locale ()) ]

-- etc.

]

Note we always pass:

- the locale value

- a value containing substitution parameters (if any).

In this case we have no substitution parameters, so we can pass any value, and

we chose the empty value () for simplicity.

First message done! You can check your project compiles and works.

Note

Generated Ftl files

A bunch of files have been generated in a Ftl folder. You shouldn’t edit

these directly, or add them to VCS. Be sure to add this folder to

.gitignore (etc.)

Substitutions¶

The next bit of our view consists of some Elm code that generates text like the following:

Hello, Mary. You have 2 unread messages.

We can split this into two messages.

Note

Splitting of localized text has to be done very carefully. One of the key principles of translating apps is that you cannot split a sentence or label into parts and translate the parts separately. This might work for English, but will fail for other languages. Usually if you have several unrelated sentences in a block of text, you can split them into a message for each sentence, but do not split up a sentence (or other text fragment like a title) further.

Our first message is a greeting, but it has a substitution. It will look like this in our FTL file:

notifications-greeting = Hello, { $username }.

And we use it like this in our Elm code:

[ H.text (T.notificationsGreeting model.locale { username = model.userName })

-- (etc.)

]

Notice how we pass substitutions in a record type. The signature for

notificationsGreeting looks like this:

notificationsGreeting : Locale.Locale -> { a | username : String } -> String

This means if you fail to pass this argument in your Elm code, or try to pass something of the wrong type, you’ll get a compilation error, which is exactly what we want to happen.

Number substitutions and plural rules¶

The next sentence we need to internationalize is "You have X unread

messages.".

The Elm code we are starting with looks like this:

H.text

(let

unreadNotificationsCount =

unreadNotifications model |> List.length

in

if unreadNotificationsCount == 1 then

"You have 1 unread message."

else

("You have " ++ toString unreadNotificationsCount ++ " unread messages.")

)

There are some big issues with this code:

- It hard-codes English language pluralization rules. In English, we use the singular form for 1, and plural form for everything else (including zero). This pattern does not apply to other languages. So we need to move this logic into the FTL file, where translators are able to apply the correct logic for their language.

- It hard-codes a number formatting function that is only appropriate for some

languages. If we were using floating point numbers, we can easily get

completely wrong number formatting. For example,

1.002(“one and two one-thousandths”) can be written in English as the string"1.002". However, in most European locales, that string means “one thousand and two”, while"1,002"means “one and two one-thousandths”.

Fluent fixes these things for us. We pull out the entire message into FTL like this, using Fluent selector syntax, to produce the following which is appropriate for English:

notifications-unread-count = { $count ->

[one] You have 1 unread message.

*[other] You have { NUMBER($count) } unread messages.

}

Our view code looks like this:

H.text

(T.notificationsUnreadCount model.locale

{ count = Fluent.number (unreadNotifications model |> List.length) }

)

This time, instead of passing a string as an argument, we pass a number. We

actually pass it as a Fluent.FluentNumber number value. The purpose of

FluentNumber is that it allows us to optionally pass formatting options

along with the number. In this case we didn’t add formatting options, so we just

used Fluent.number. We could have used Fluent.formattedNumber to

specify formatting options (which includes things like currencies).

It is also possible for the translators to add parameters using the NUMBER builtin.

Similarly, not covered in this tutorial, there is the Fluent DATETIME builtin, and elm-fluent functions Fluent.date and Fluent.formattedDate which are used to pass dates into messages.

Message attributes¶

The next piece of HTML we need to internationalize is the search box. The Elm code looks like this:

viewSearchBar : Model -> H.Html Msg

viewSearchBar model =

H.div []

[ H.input

[ A.type_ "search"

, A.name "q"

, A.placeholder "Search"

, A.attribute "aria-label" "Search through notifications"

, A.value model.searchBoxText

, E.onInput SearchBoxInput

]

[]

]

We can continue with this in exactly the same way as before — creating a message

for each piece of English text that needs to be translated. One need that often

crops up in web apps is that we have some closely related pieces of text, and we

might want to group them more tightly. In the case above we have two pieces of

text that appear as part of the search box - "Search" as the placeholder,

and "Search through notifications" as the ARIA label, which will be used by screen

readers.

There is a Fluent feature designed exactly for this case, called attributes. We can create an FTL message as follows:

notifications-search-box =

.placeholder = Search

.aria-label = Search through notifications

This will create two message functions for us. In this case, to produce valid

Elm identifiers, the . is translated to an underscore, so we end up with

notificationsSearchBox_placeholder and notificationsSearchBox_ariaLabel.

These can be used in the same way as before, so our Elm code becomes:

viewSearchBar : Model -> H.Html Msg

viewSearchBar model =

H.div []

[ H.input

[ A.type_ "search"

, A.name "q"

, A.placeholder (T.notificationsSearchBox_placeholder model.locale ())

, A.attribute "aria-label" (T.notificationsSearchBox_ariaLabel model.locale ())

, A.value model.searchBoxText

, E.onInput SearchBoxInput

]

[]

]

This example also illustrates the use of localized text in attributes — because our translation functions simply return strings, their output can be used in a wide variety of contexts.

HTML output¶

Although string output is the most flexible, there are times when you need HTML output.

For example, we may simply want to highlight some text in some way. Suppose in our greeting we want to highlight the username in bold:

Hello <b>Mary</b>, so nice to have you back!

Remember that a key rule of i18n is that we mustn’t attempt to split this into parts, translate separately, and put back together. We need to keep these parts together as a single, translatable unit.

This is handled in elm-fluent simply by giving the message ID a special suffix -

-html or Html — and then putting the desired HTML markup directly in the

.ftl file:

notifications-greeting-html = Hello <b>{ $username }</b>, so nice to have you back!

In this case, ftl2elm will generate a function which returns List (Html

msg) instead of String. You can use it just as you expect, e.g.:

H.p []

(T.notificationsGreetingHtml model.locale { username = model.userName } [])

Note, however, this takes one extra parameter, for which we passed an empty list. The purpose of this parameter is explained in the next section.

Before we go on, there are a few things to note:

Compare the combined FTL + Elm you have above with what you would have had before if you had written it all in Elm:

H.p [] [ H.text "Hello " , H.b [] [ H.text model.userName ] , H.text ", so nice to have you back!" ]

You may notice that your code, even when you add back in the FTL, is now shorter and much more readable! This is just a little bonus that comes from using a purpose-designed language like FTL, and a compiler (ftl2elm) that will generate all that

Htmlcode for you…elm-fluent can handle a lot more than this simple case — all the other Fluent features can be combined with HTML. This includes also being able to use attributes in the HTML, and substitutions within attributes etc.

There are a few limitations. You cannot have substitutions or other similar constructs in element names or attribute names, for example:

bad-message-1-html = Some <{ $arg }>text</{ $arg }> bad-message-2-html = Some <b { $arg }="value">text</b>There are also limitations with respect to Fluent’s mechanism for message references. You can reference both HTML and plain text messages from HTML messages, and it will do the right thing, but you cannot reference an HTML message from a plain text one. (This might be obvious from the type system - we can embed

StringintoList (Html msg)viaHtml.text, but we can’t embedList (Html msg)intoString.You should consider carefully how much HTML you should put into your FTL files, and keep it as simple as possible. Remember it will be read and translated by translators who may not be experts in HTML. Use the mechanisms described in the next section to keep as many HTML attributes in your Elm code as possible.

Dynamic HTML output¶

The above mechanism works fine for simple cases, but in Elm we often have more

complex HTML, and in particular we have Html constructs that cannot be

simply embedded into FTL files as a string.

For example, in our demo app, when you press the ‘Delete’ button, you get a confirmation panel that has hyperlinks like this:

These 2 messages will be permanently deleted - cancel or confirm

…except that ‘cancel’ and ‘confirm’ are hyperlinks with behavior attached. The original Elm code looks like this:

[ H.text "These " , H.text <| toString <| Set.size model.selectedNotifications , H.text " messages will be permanently deleted - " , H.a [ A.href "#" , onClickSimply DeleteCancel ] [ H.text "cancel" ] , H.text " or " , H.a [ A.href "#" , onClickSimply DeleteConfirm ] [ H.text "confirm" ] ]

We need the a elements to be embedded in translatable text (as discussed

above — we don’t want to split this text up). But we also need a way to attach

those event handlers to the anchors, and we need to ensure we don’t mix up those

event handlers.

(Also, we got lazy above and didn’t handle the case of a single message very well — we’ll fix that as we go).

This is probably one of the most complex examples you’ll come across, so the next section will be a little bit heavy. But if you can master this you have the tools to handle any similar situation.

Let’s start with a first attempt at our FTL message:

notifications-delete-confirm-panel-html =

{ $count ->

[one] This message

*[other] These { $count } messages

} will be permanently deleted - <a>cancel</a> or <a>confirm</a>

and our Elm code to call it:

T.notificationsDeleteConfirmPanelHtml model.locale { count = Fluent.number <| Set.size model.selectedNotifications } []

This will produce the right text, but the ‘cancel’ and ‘confirm’ parts don’t do anything, or even look like links yet.

If you look at the type signature of the generated

notificationsDeleteConfirmPanelHtml, you’ll find this:

notificationsDeleteConfirmPanelHtml : Locale.Locale -> { a | count : Fluent.FluentNumber number } -> List (String, List (Html.Attribute msg)) -> List (Html.Html msg)

That final parameter looks a bit intimidating, but it is simply a way of passing the attributes that we would have attached directly before. To break it down, it is a list of tuples, where each tuple consists of:

- A string element, whose value should be a CSS selector (a very limited subset of CSS selectors, to be precise)

- A list of attributes that are attached to the elements that match those CSS selectors.

So, for a start, for our a elements to be actually rendered as hyperlinks,

they need an href value. Both anchors match the CSS selector a, so let’s

replace that final empty list with:

[("a", [ A.href "#" ])]

Rebuild, and you’ll find the two a elements at least appear as links.

We now need to attach the event handlers. In most cases, in a single piece of translatable text we would only have a single link or ‘active’ element that needs attributes, so we would just add more attributes to the list above — like this:

[ ( "a", [ A.href "#"

, onClickSimply DeleteConfirm

] )

]

But in this case we need to attach different handlers to the different elements,

and they are both anchors. This means we will need to change the FTL message so

that the two a elements can be distinguished somehow.

To enable this, elm-fluent supports a subset of CSS selectors. The full list is:

| Type | Example |

|---|---|

| element | a |

| class | .foo |

| id | #mything |

| attribute present | [data-bar] |

| attribute value | [data-bar=”value”] |

| element and class | a.foo |

| element and id | a#mything |

| element and attribute present | a[data-bar] |

| element and attribute value | a[data-bar=”value”] |

For our purposes, we’re going to add two adhoc data- attributes to our

message — plus an explanatory note for the translators. We’ll actually start

them both data-ftl- — these attributes will appear in the final rendered

HTML, and we probably want to avoid clashing with other data- attributes we

might be using for other purposes. So our FTL looks like this:

# Confirmation message when deleting notifications.

# It includes two hyperlinks - 'cancel' to cancel the deletion,

# and 'confirm' to continue.

# You must wrap the 'cancel' text in:

#

# <a data-ftl-cancel>...</a>

#

# and wrap the `confirm' text in:

#

# <a data-ftl-confirm>...</a>

#

notifications-delete-confirm-panel-html =

{ $count ->

[one] This message

*[one] These { $count } messages

} will be permanently deleted - <a data-ftl-cancel>cancel</a> or <a data-ftl-confirm>confirm</a>

Our Elm code becomes:

T.notificationsDeleteConfirmPanelHtml model.locale

{ count = Fluent.number <| Set.size model.selectedNotifications }

[ ( "a", [ A.href "#" ] )

, ( "[data-ftl-cancel]", [ onClickSimply DeleteCancel ] )

, ( "[data-ftl-confirm]", [ onClickSimply DeleteConfirm ] )

]

That’s it! The generated code in notificationsDeleteConfirmPanelHtml takes

care of adding the passed in attributes to the right nodes, so you get the same

functionality as before.

Let’s just take stock of what we have to do for these cases:

- Pull out the text and the essential HTML structure into FTL.

- For all the attributes we were attaching before, create a CSS selector to match the HTML node they should be attached to, and put them together in a tuple, passing the list of tuples as the final parameter to the message function.

- If necessary, add some attributes to the HTML in the FTL file to disambiguate the HTML nodes, and adjust the CSS selectors accordingly.

The result is that we have a clean separation of concerns. Our localized text is in one place, and it has the flexibility to structure the text and any embedded HTML in any way necessary for the language. The text is actually much more succinct and readable than before.

Our behavior is still all defined in Elm, though, where we want it. Admittedly it has become more dense, but we’ve only had to make simple, local changes.

Note

Performance

This use of CSS selectors might make some people worry about performance. Is there some heavy HTML parsing going on behind the scenes?

In reality, all the HTML parsing happens at compile time i.e. when

ftl2elm runs. We know at compile time the exact list of supported CSS

selectors that each node can match. For example, if we have <a

class="foo"> in the FTL, the complete list is a, .foo and

a.foo. The generated code for that node does a simple List.filter on

the passed in attributes to find these 3 selectors. This is a little bit more

expensive than the original code, but there isn’t any heavy lifting going on

at runtime.

Final steps¶

Having now completed our English notifications.ftl file, the next step is to

distribute this to translators, so that they can produce similar ones, but in

the target languages. When returned, these will be added to your project in new

directories under locales using the same structure as before and committed

to source control (like the original).

Finally, we can use ftl2elm to compile everything as part of our deployment

process. ftl2elm can pick up quite a few errors in FTL files itself, and

will complain loudly by default and fail. Other errors will be picked up by the

Elm compiler (e.g. missing arguments to messages), to ensure that you can’t

deploy with broken translations.